How Near-Shoring Can Help the U.S. To Outmuscle China in the Global Economy Competition

The Mexican Example

Mexico has just overtaken Canada and China as America’s top trading partner. It has also surpassed most members of the G20 in 2023 in terms of economic growth on a per capita basis, figures, which do not even include its shadow economy or the value of illegal drugs that transit through the country into the United States. The facts are that crime aside, Mexico grows economically because it replaces China as an offshore manufacturing haven. Factories in its industrialized north can export to the U.S. tariff-free, including Chinese-owned ones, and this trade advantage is behind an economic boom that began in 2020. Since then, Mexico’s GDP per capita (129 million people) has increased from $8,770 to $13,804 in 2023 and heads toward $17,287 by 2028. Tourism, agriculture, and retirement havens also contribute to this growth, but figures also reflect the income made by those who work for, or service, Mexican drug cartels. Today, there are two Mexicos — one firing legitimately on all economic cylinders — and the other feeding America’s bottomless appetite for illicit drugs. One is creating a prosperous middle class and the other undermines Mexican institutions and turns parts of the country into a war zone.

Mexico has roughly the size of Western Europe.

On January 17, 2024, the Yucatan Times reported that 30,000 murders, mostly drug-related, were committed in Mexico in 2023, an average of 84 daily. “In total, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s six-year term has accumulated 166,193 murders and 4,892 femicides since December 2018,” according to figures from the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System (SESNSP).” The figures are shocking, but Mexico has always had a violent, troubled history, mostly due to drug smuggling.

But Mexico even so, overtook China as the leading trade partner of the U.S. in 2023, and that signaled a geopolitical and economic shift with far-reaching potential implications from just registering a mere statistic fact.

While Mexico’s exports to the US market rose by 4.6%, Chinese exports plummeted by 20% over the previous year, putting Mexico in first place.

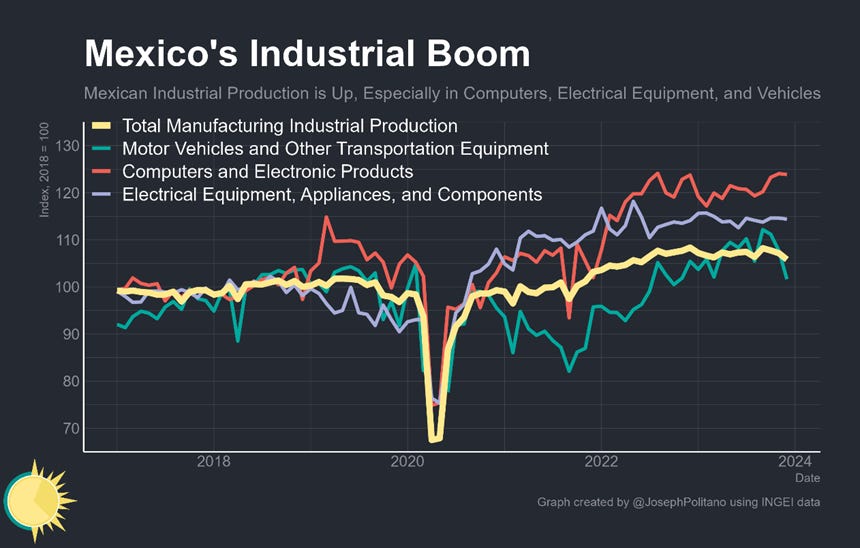

The driving factor for Mexico becoming top U.S. trading partner in 2023 was its industrial export growth:

The macro basics for this change came from two main fundamentals.

First, the signing of the 1994 NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement), replaced by the USMCA in 2020, allowed Mexico to enjoy the advantages of immediate geographic proximity, low costs, close diplomatic ties, and near-zero tariffs on its exports to the other NAFTA members, the United States and Canada, and it seemed a natural and complementary trade partner. The peso crisis that hit Mexico shortly after the NAFTA signing was a setback, as was the 2000-2002 crisis and the Great Recession, yet there had been plenty of years for the dynamic Mexican economy to recover and soar. But in 2001 China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). A combination of very low Chinese wages and prices, the manipulation of China’s currency to make its exports very attractive, and technological advances that reduced ocean shipping costs meant that China was able to shoulder its way past Mexico in 2004-2006 and become the biggest trade partner of the United States. In a sense, it could be said that China’s explosive entry into the global trade scene stole Mexico’s promise. The hope of NAFTA was that as Mexico began to exercise its comparative advantage in manufacturing, it would not only become the key US trading partner, but wages and employment would rise in Mexico in the sectors that were engaged in NAFTA trade. For comparison, versus the near-zero tariffs of Mexico on its exports to the other USMCA members, the customs tariffs levy Chinese imports in the U.S. up to 37% nowadays as the average levy is 19.3%. The levies cover approximately $335 billion in trade (66.4 percent of China’s exports to the U.S.) that remains subject to the tariffs.

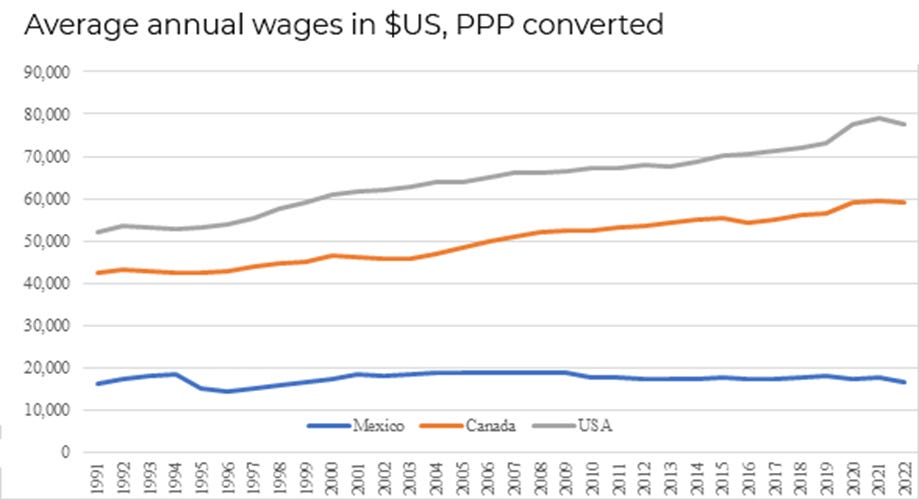

Second, the wage level in Mexico is identical to the Chinese one. The average salary in Mexico is around 350,000 pesos yearly. When converted to USD, this is around $17 000 USD yearly or $1 417 monthly (Average Salary in Mexico [2023 Guide] (joinhorizons.com)). In Q2 2023, the average salary in 38 Chinese cities was ¥10,266 RMB ($1,430 USD) per month (Our 2023 Complete Guide to Salaries in China - TeamedUp China). However, the growth trend of the wages in Mexico is lower and more conservative than the Chinese one (https://data.worldbank.org/assets/images/placeholder.png) as well as lower and almost flat versus the US and Canadian ones:

Source: OECD

These two macro fundamentals were smartly used by the Mexican government. It has prioritized construction and manufacture as key drivers of its policy for GDP growth, respectively for the national export augmentation.

Mexico’s construction boom has been strongest in the southern states, historically among its poorest, where many of those public works megaprojects are currently underway. First is the Tren Maya, a new rail network throughout the Yucatan peninsula primarily designed to connect Cancun and other coastal tourist destinations with historic Mayan sites and various cities further inland. Then there is the Dos Bocas refinery complex in Tabasco, owned by national oil company PEMEX and designed to increase domestic crude processing capacity while reducing Mexico’s dependence on imported fuels. Finally, there is the Tehuantepec Isthmus Interoceanic Corridor (CIIT), a network of ports, railways, highways, and industrial parks designed to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, compete with the Panama Canal, and kickstart a regional manufacturing hub.

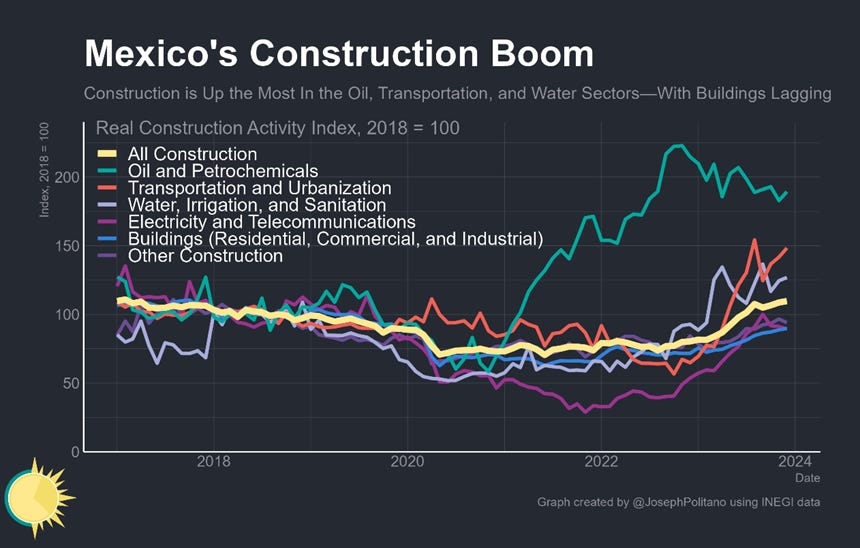

Thanks to Dos Bocas, Tren Maya, and CIIT, real construction activity in the oil and petrochemical sector has doubled compared to 2018 while real construction in the transportation and urbanization sector has increased by nearly 50%. These megaprojects by no means represent the entirety of the public works push either—real investments in electricity, telecommunication, and water infrastructure have also risen significantly over the last year. In contrast, overall construction of buildings has been relatively low, held back by an extremely weak residential sector that has still not recovered from COVID.

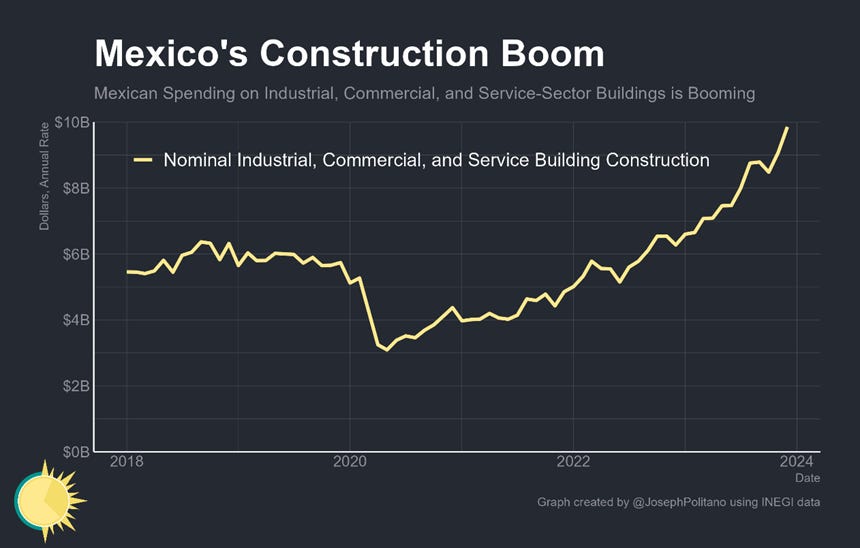

However, the decline in overall investments in new buildings belies significant growth in business spending on factories, warehouses, storefronts, and other facilities. Nominal spending on industrial, commercial, and service building construction is booming, already rising more than 50% from pre-COVID levels and approaching a rate of nearly $10B a year—meaning it now exceeds total spending on domestic residential construction. Obviously, the construction boom comes from the industrial one:

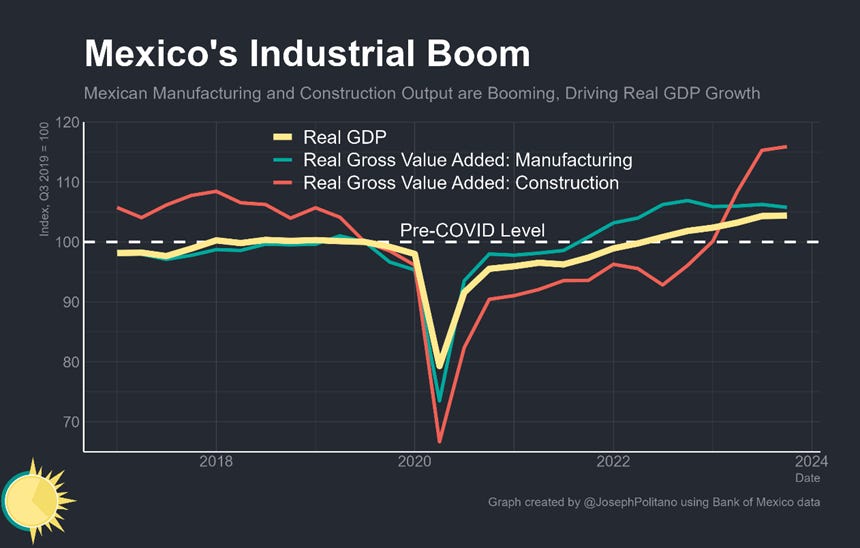

That construction boom has helped Mexico’s economy break out of a long period of relative stagnation—GDP had been stuck at or below 2018 levels for years before growing 4.5% in 2022 and another 2.4% in 2023. Since the start of the pandemic, real gross value added has increased by more than 15% in the construction sector and by nearly 6% in the manufacturing sector, especially in industries like motor vehicles, electronics, electrical products, and home appliances. Indeed, Mexico has a unique advantage in that it can benefit directly from US policy efforts to decouple key industries from China and near-shore manufacturing supply chains while shouldering less of the economic cost of American trade restrictions and Chinese retaliations. All that made Mexican construction growth very different from the recent Chinese one – while the Mexican construction sector served mainly the national industrial growth, the Chinese had to compensate the industrial stagnation after 2010 in the national economy.

Nevertheless, manufacturers of Chinese goods are increasingly shipping via Mexico in order to avoid the impact of tariffs on imports directly to the U.S.

A review of customs data by the Financial Times (FT) and Xeneta revealed the number of 20-foot containers shipped from China to Mexico reached 881,000 in the first three quarters of 2023, up from 689,000 in the same period of 2022.

It was suggested that many of the goods imported are then moved onto trucks in order to complete their journey, as evidenced by growing numbers of cross-border shipments from Mexico to the U.S.

The publication noted that direct shipments to the U.S. from China have fallen from around a fifth of the US' total imports in 2017 to around 15 percent today, following the introduction of new tariffs by the administration of Donald Trump, many of which have been retained or expanded on by current president Joe Biden.

Erik Devetak, chief product and data officer at Xeneta, told the FT: “Reducing reliance on China is an easy sound bite for politicians, but the reality is very different.”

He added that a true realignment of manufacturing to cut the U.S.' dependence on Chinese goods would be "a vast undertaking which will take many years and a colossal amount of investment and state intervention to achieve”.

Among the main beneficiaries of using Mexico as a stop on the supply chain is China's auto manufacturing sector. Figures from the INA, Mexico’s trade body for auto parts suppliers, show that there were 33 Chinese-owned companies with Mexican operations in 2023. These shipped $1.1 billion worth of parts to the U.S., up from $711 million in 2021. Meanwhile, Mexico imported almost $9 billion of vehicle parts from China last year.

Currently, cars and auto parts shipped directly to the U.S. from China are subject to tariffs of 25 percent. However, automobiles manufactured in Mexico only attract a 2.5 per cent US levy, while parts put together in Mexico incur tariffs of between zero and six percent.

The re-export at expense of the export revenue cashing in of course pushes down further the well - known low productivity of Chinese economy.

Besides, the FT noted that Mexico is looking to address the issue, introducing its own tariffs of between five and 25 percent on Chinese imports last year, but added it is unclear how effectively these will be enforced. The tariffs should help Mexico to diminish its strongly negative foreign trade balance with China (above 100 billion US dollars in 2023). The biggest importer in the country however is the U.S. with a share of 45% of the total import, followed by China – 20% and South Korea – 3.6% (Mexico Imports By Country (tradingeconomics.com). Otherwise, Mexico is highly open to foreign trade, which represented 88% of its GDP in 2022 (World Bank, latest available data). The country mainly exports cars (8.1%), automatic data-processing machines (7.4%), vehicle parts (6.6%), vehicles for the transport of goods (5.7%), and petroleum oils (5.5%). This openness enabled the country to attract $110.7 billion as foreign direct investments (FDI) in 2023. Mexico manufactured only 106k EVs last year, but was still America’s third-largest source of imported EVs, and right now Tesla is looking to build a major factory in Nuevo León (estimated investment of $10 billion). The Chinese EV giant BYD is also considering opening production facilities in country. CHIPS Act spending on semiconductor facilities, especially in the American southwest, could identically benefit Mexico’s rapidly growing electronics industry. Manufacturing of computers has already risen 60% over the last 5 years, and production of semiconductors and other electronic components is up 30%. So far, America’s renewed focus on industrial policy has genuinely benefitted its southern neighbor, although it is yet to be seen whether it can help kick-start a greater transformation of Mexican industry (this transformation is still not quite seen in the U.S. unfortunately).

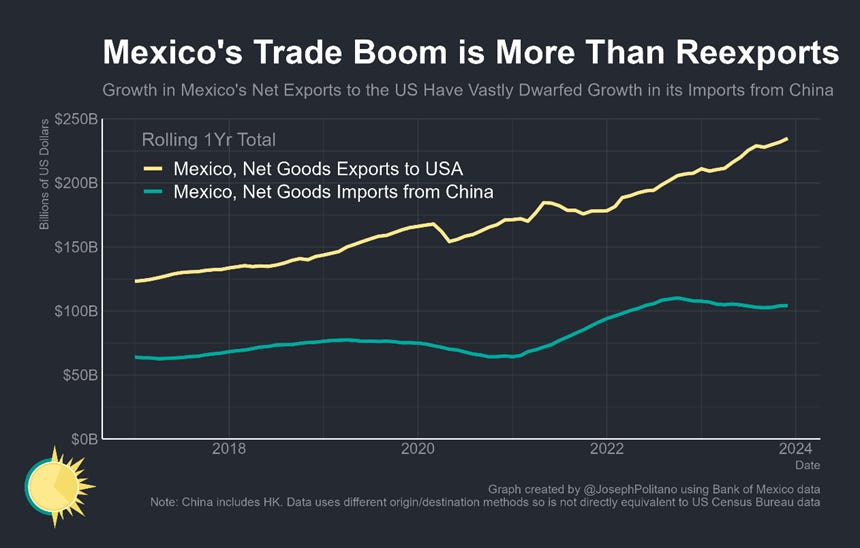

But even so, what happens in the Mexican industry has already been paying dividends—Mexico’s northbound net goods exports closed out last year above $225B, a record high despite the country’s increasing imports of American natural gas and other energy products. Of course, the great fear is that Mexican factories are used only for small amounts of packaging and final assembly activity to circumvent tariffs on what are still fundamentally Chinese goods—but so far, that fear has been largely unfounded. Mexico’s net imports from China have grown by significantly less than its net exports to the US, and much of Mexico’s rising imports reflect strong domestic spending on consumer goods and equipment rather than intermediate inputs. Indeed, Mexico’s overall share of value-added in its manufacturing exports has remained relatively constant over the last 5 years even amidst the near-shoring boom. In other words, Mexico is already benefitting from more active US industrial policy and has a chance to become an even larger presence in American markets—if it can play its cards right.

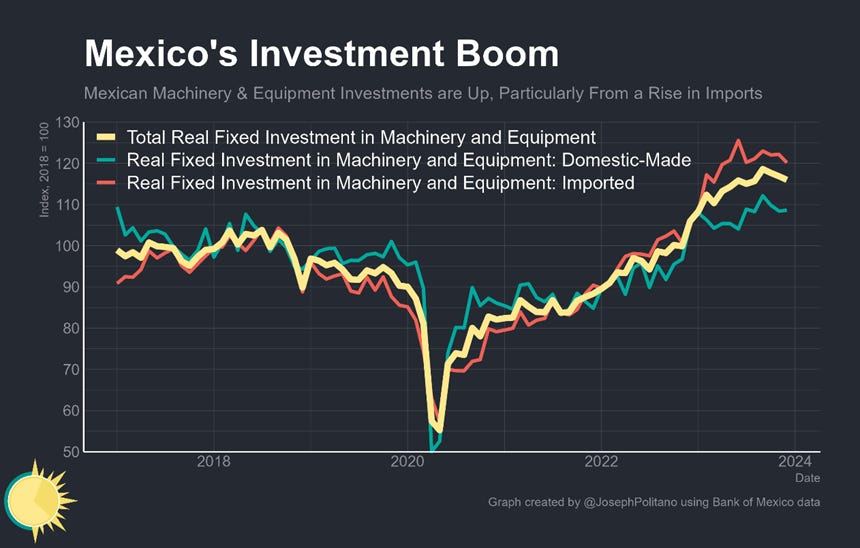

Despite of it, the Mexican export and overall industrial growth still is impossible without a significant import of machines and equipment as well as other products input.

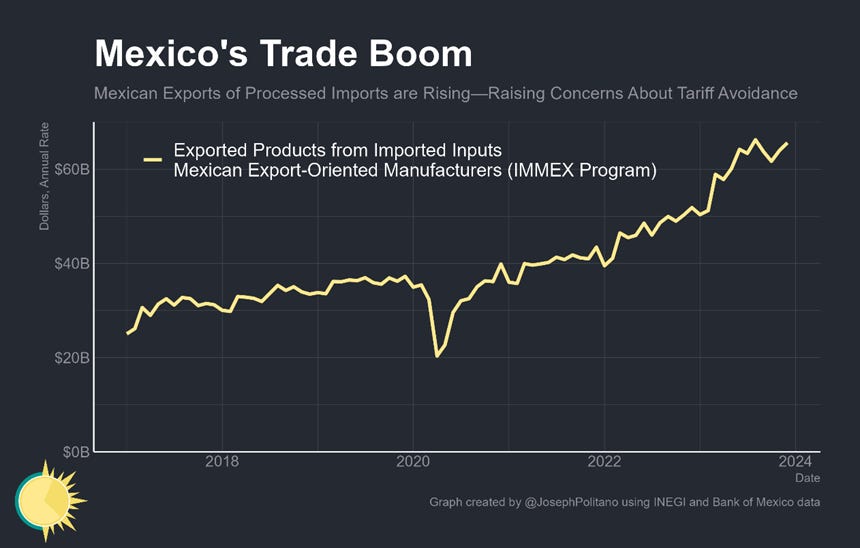

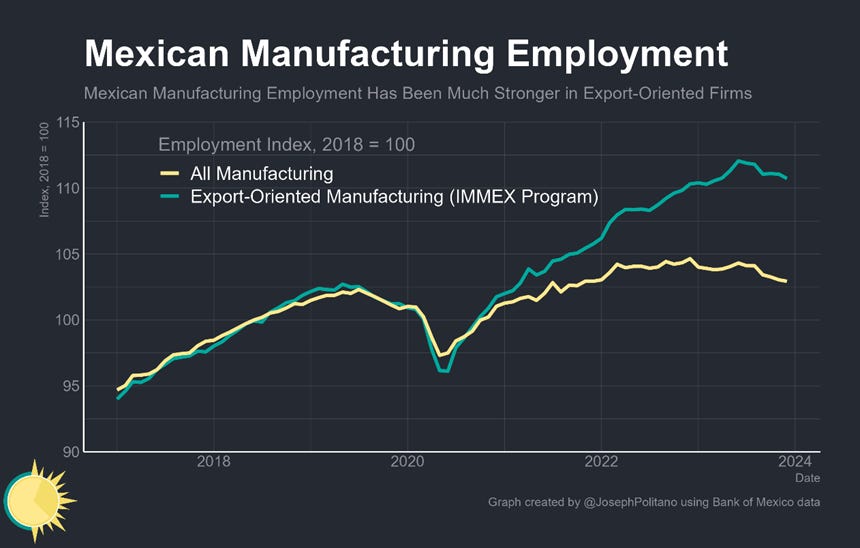

Complementing the growth in fixed investment has been a rise in Mexico’s manufacturing exports—by the US government’s count, Mexico surpassed China as America’s number one source of gross imports last year. But to what extent is Mexico genuinely benefitting from that export boom—and to what extent is it just serving to re-export foreign goods while adding little to the production process? Mexico’s export-oriented firms—participants in the IMMEX program (aka Maquiladoras) who receive reduced taxes and preferential treatment to manufacture goods in Mexico for final consumption abroad—have seen a significant increase in revenue from foreign sales of goods made with imported inputs.

But this data again raises alarm bells for those concerned about tariff avoidance and leads to doubt about the actual underlying strength of Mexico’s export industry. It is likely not true, for example, that Mexico has truly passed China in gross exports to the US, as the trade data does not track the increasingly common extremely small ‘de minimis’ shipments from companies like Temu and Shein and is likely significantly undercounting Chinese exports due to tariff avoidance. Plus, America’s net imports from China still dwarfed its net imports from Mexico last year, and Mexico does not have the dominating global market share in key industries that China has.

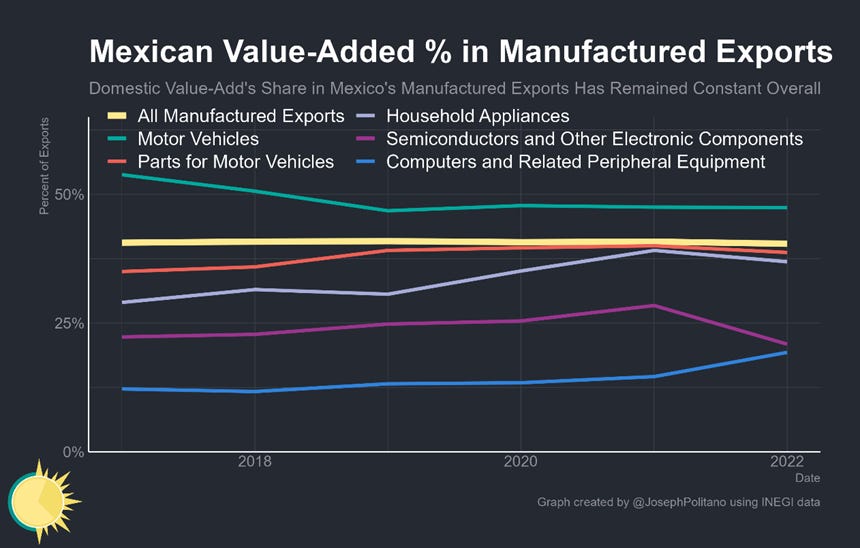

Yet on the top of it, it is still true that the majority of Mexico’s export boom is genuine—most tariff avoidance would go through countries elsewhere in Asia and many of the sources of rising Mexican exports are in industries where China has little presence in the North American market, like motor vehicles. It is also obvious when you look at Mexican manufacturing output—overall production has risen by 5% since 2018 but has been even stronger in export-oriented industries—Computer output is up nearly 25%, appliance and electrical equipment output is up 15%, and motor vehicle production has more than recovered from the effects of the semiconductor shortage. The value added data about Mexican industry also confirms this conclusion because only the manufacture of parts for motor vehicles could directly be connected with Chinese stuff re-export:

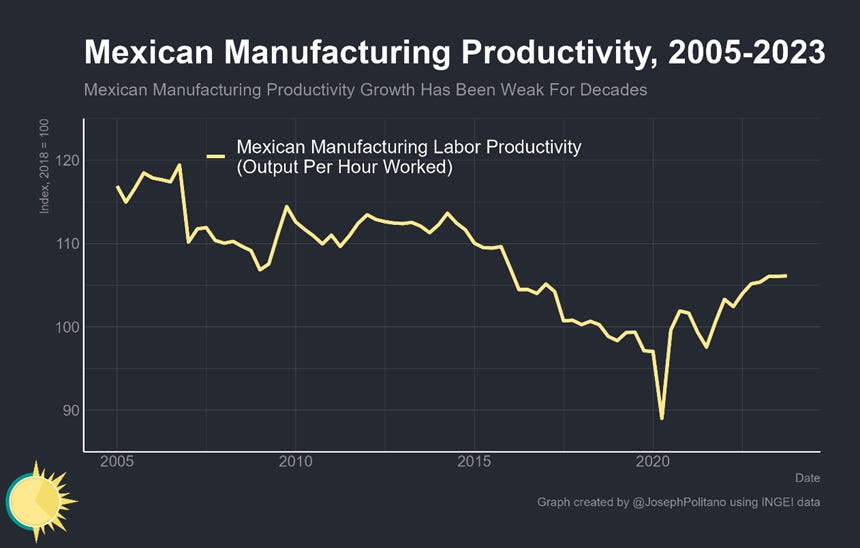

The last two charts combined however bring to attention the key problem of the Mexican industry, which is similar to the Chinese one – the industry is developing under low productivity (product niches growth and attributed to it low value added). In this aspect, the historic trend is not encouraging for Mexico either:

But even under low productivity the Mexican manufacturing employment, while relatively weak overall, has been strongest in the export-oriented businesses that now make up roughly 60% of manufacturing jobs. Since 2018, employment in manufacturers who participate in the IMMEX program has risen by more than 10% while total manufacturing employment has risen by less than 3%.

Then yet even amidst the growth of near-shoring, Mexico’s overall share of value-added embedded in its manufacturing exports has remained practically constant throughout the last 5 years. Among major industries, there has been a slight decline in Mexico’s share of value-added in motor vehicle exports and a slight increase in its value-added in the vehicle parts and appliances sectors. Perhaps most notable are the shifts in the electronics sectors where Mexican value-add tends to be low, particularly an increase in computer value-added and a decrease in semiconductor value-added. Given how volatile the semiconductor market has been over the last few years this may be just a blip, but it will still be key to watch amidst US semiconductor sanctions and the CHIPS build out. Overall though, it is clear that the rise in Mexican exports largely represents genuine growth in manufacturing activity rather than simply a middleman arrangement. Nevertheless, the low productivity is still a structural problem for the Mexican manufacturing sectors.

The future Mexican president will inherit an economy that has significant structural problems indeed —Mexican per-capita GDP growth has been weak for decades, not helped by a manufacturing sector that has generally gotten less productive even as it has grown. Getting a proper return on investment for all the infrastructure spending will be extremely difficult and require prudent economic management, especially considering how far over budget many projects have gone and the large public debts incurred by PEMEX and the national government. Concerns about the economic impacts of deteriorating domestic security and possible corruption are rising, and forecasters already expect the country’s GDP growth to slow this year.

Plus, of course, there is the upcoming US presidential election, where Mexico has more at stake than perhaps any other country. While the current administration sees the growth of made-in-Mexico goods as a success of friend-shoring, not everyone in Washington shares the same definition of friend. Trump—who had previously threatened Mexico with tariffs in immigration negotiations as President, imposed stricter automotive manufacturing requirements as part of the USMCA deal, and is now advocating for universal baseline tariffs—will certainly look more unfavorably on Mexican industry if elected president. However, still, Mexico has the opportunity to make the best of this friend-shoring moment, especially given America’s ravenous goods demand and its post COVID economic outperformance over other major global economies.

In fact, the most appealing aspect of Mexican near-shoring (friendly-shoring) is that the country can partner the U.S. in a win – win solution versus global Chinese geopolitical ambitions without its government even to control the whole territory of the state. To top it off, it has been put to apply its industrial endeavours within an environment of traditional corruption while making war in it with the local narco-cartels. The Mexican success however became possible after the government chose the right model for industrial development, it was supported by the US economy with massive investments and the Mexican companies could rely on the big American domestic market for their export under favourable custom tariffs. Practically the U.S. outmuscled China in Mexico with corporate investments. And it happens again in South East Asia. There China comes as third big investor in the ASEAN economies after the U.S. and the EU. Investment outmuscling brings the Chinese export surpluses to gradual drying up in parallel with Chines domestic demand dip (China’s double whammy: Exports fell for the first time in 7 years, as domestic demand dips | CNN Business). Therefore, the friendly-shoring based on the investment outmuscling in the most dynamic regions of the global economy is the best formula for holding back the Chines industrial overproduction used by Beijing as an economic weapon (https://stoev.substack.com/p/chinese-economy-as-a-geopolitical) for global expansion and democracy undermining. Further, the investment outmuscling in friendly-shoring is the most sustainable response of the West to its trade deficit with China and Chinese attempts to control international supply chains. Its value as counter-weapon fits well also with the current Western superiority over Beijing in sectors like chip making, computers manufacture and military potential. Investment outmuscling can be replaced by no means with only restrictive custom tariffs application and lowering the tax levies for the rich people in America as Trump intends (https://stoev.substack.com/p/trump-is-a-disaster). The Mexican example attributed with all its current problems confirms this conclusion.