The first 100 days of Trump’s presidency in the White House marked a decline in the US GDP, a fact that makes a clear contrast to what occurred during the initial quarters of the post-COVID pandemic years:

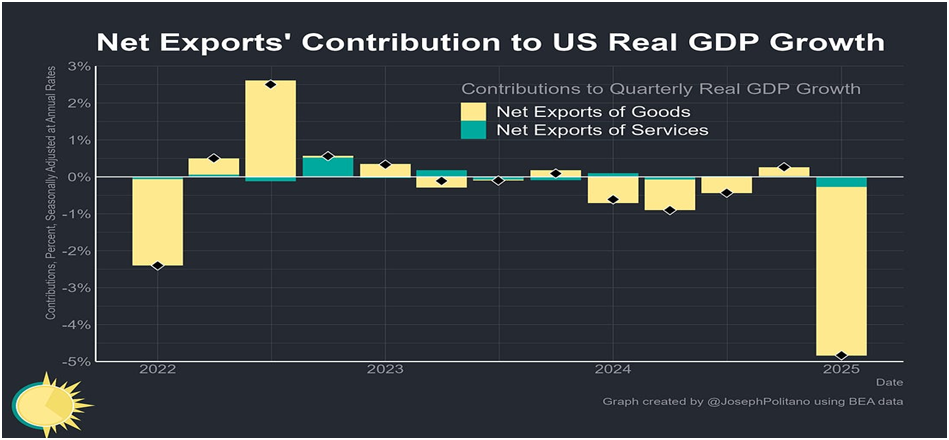

The main contributors to the GDP decline were the worsening net export indicator and the cut in government spending:

The chart above also shows that consumption was closer to or less than ordinary levels, and investments went significantly upward. But the net export plummeted both in the goods (more essentially) and services sectors:

Then, if we have to analyse further the investments as an eventual positive sign apart from the overall growth decline reality, we should not be extremely positive about any assumption that a structural change was underway in the US economy under Trump:

What we can see from the last chart is that fixed investments, residential and non-residential, were identical or even smaller than those earlier, but the big change came from the rise in the private inventories. The latter influenced the trade deficit in such a way that net exports notched their largest quarterly decline since records began in 1947, an achievement quite the opposite of the declared priority of the President for deficit reduction. Now, it is important to clarify that this import surge does not itself shrink the economy—GDP is an estimate of domestic production, and is not affected by purchases from abroad. Yet domestic production is difficult to measure directly, so GDP is estimated by summing consumption, investment, government output, and exports while subtracting imports only to prevent double-counting. Thus, consumers rushing out to buy foreign-made clothes will show up as an increase in imports (a negative “contribution” to GDP) and an increase in consumption (an equal-and-opposite positive “contribution” to GDP) and have no net effect on economic growth.

In this case, however, the surge in imports primarily manifested as a surge in business inventories—it was corporations, not consumers, doing most of the stockpiling. The positive contribution from inventory growth was the highest since late 2021, “offsetting” a bit less than half the jump in the trade deficit. Fixed investment of foreign equipment also helped significantly “offset” the increase in imports at the start of this year.

Yet it is also important to say that the costs and uncertainty of trade policy chaos can have real negative growth effects. If a construction company rushed to buy a bunch of wood from Canada ahead of tariffs, that would show up as an increase in imports and an increase in inventories which cancel each other out. But if that company slowed down construction so it could afford to stockpile inputs, that would show up as a hidden drag on GDP in the form of lower investment. In other words, tariff front-running can indirectly slow the economy, and that is exactly what we saw at the start of this year.

Real imports of goods shot up to a record high at the start of 2025, rising nearly 11% from the end of 2024. The only recent trade shifts of a similar scale are the COVID pandemic and the 2008 recession, yet while those events caused unprecedented contractions in trade, the threat of tariffs has done the exact inverse and caused trade to surge at a speed not seen in 50 years, especially in the IT and pharma sectors:

In this case, however, the surge in imports primarily manifested as a surge in business inventories—it was corporations, not end consumers, doing most of the stockpiling.

Breaking Down the Import Surge

Computers & pharmaceuticals were the two sectors behind the vast majority of that record import surge—outside those industries, the jump in imports was noticeable but not record-breaking. Pharmaceuticals, an industry Trump has long promised to hit with tariffs on but has exempted from nearly all trade policy actions so far, saw their real imports jump 60% from their previous record high. On the other hand, computers were not specifically targeted by Trump in the same way as pharmaceuticals during Q1, but they were heavily dependent on a Chinese & broader East-Asian supply chain that risked heavy disruption from tariffs. Real imports of laptops, desktops, and other computers thus rose by more than 50% in Q1 2025 as companies tried to prepare for disruptions to their complex supply chains. Where did all those drugs and electronics go?

The pharmaceuticals were mostly stockpiled by medical companies—drug wholesalers’ inventories rose by the highest amount ever recorded, beating the previous record-high. In fact, the rise in pharmaceutical inventories was so large that it was single-handedly responsible for nearly 40% of the total increase in inventories across the entire US economy. This is downstream of both genuine stockpiling of the range of medicines made only outside America and a rush by drug multinationals who use transfer pricing schemes to book as much profit as possible in Ireland, Switzerland, Singapore, and other low-tax jurisdictions before the tariffs kick in. This record pharmaceutical stockpiling is also far from over, as preliminary data from the EU countries responsible for most US drug imports shows even larger increases on the near horizon.

By contrast, the record-high imports of computers were mostly driven by rising investment at AI labs and other tech companies, not by business inventory growth or consumer electronics spending. Fixed investment in computers & peripheral equipment rose 21% in Q1 to a new record high as firms continue investing more and more in computing capabilities. In fact, computers & broader information processing equipment were responsible for more than 70% of the increase in total fixed investment this quarter. This import surge is also unlikely to slow anytime soon—even though Trump has promised tariffs on computers, semiconductors, and electronics at some indeterminate point in the future, at the moment most computers used for AI training come from either Taiwan or Mexico and remain totally exempt from tariffs.

The Other Bits of GDP

Outside of the rapid shifts in trade itself, consumption growth also changed considerably at the start of this year. Spending on motor vehicles and parts had their worst quarter since mid-2021, mostly as a come-down from the rapid growth at the end of 2024. This was one area where tariff front-running was extremely early, with consumers rushing to buy cars before Trump even took office. This led to muted car sales in January/February, only partially offset by the rapid increase in sales after Trump officially announced auto tariffs in March. Meanwhile, spending on pet supplies, toys, cosmetics, clothes, and other miscellaneous non-durables kept growth in that category relatively normal. Finally, services consumption had the smallest contribution to GDP growth in a year and a half, thanks to slowdowns in healthcare and food services spending.

DOGE cuts to federal employment and grantmaking also shrank public-sector output in Q1 for the first time since mid-2022, with both major categories of federal activity contracting. Defence output had its worst quarter in years amidst cuts to spending on civilian employees and miscellaneous military supplies, while nondefense output also shrank due to employment cuts. Finally, cuts to federal education and health grants also dragged heavily on state & local activity.

Yet even amidst all of this chaos, “core” American economic growth has held up relatively normally. Real final sales to private domestic purchasers—a mouthful of a term that just represents the sum of private-sector consumption & fixed investment—grew at a standard rate of 3%. These metrics are not wholly untainted by the effects of trade policy (the increase in fixed investment is mostly from tariff-driven computer imports, for example), but provide evidence that the economy has not yet entered a recessionary spiral. Going forward, volatility in overall GDP will be extra high given the wild swings in imports and inventories, so keeping an eye on the health of these “core” metrics will be critical.

This data does not predate all of Trump’s tariffs—taxes on Chinese imports were already 20% by the end of Q1, tariffs on non-USMCA-compliant imports from Mexico/Canada were 25%, and the steel & aluminum tariffs had also gone into effect—but it does predate the entirety of the massive April 2nd tariff hikes. In other words, the economic shifts seen in these numbers are mostly from the threat and uncertainty surrounding tariffs, not from the actual tariffs themselves. Trade policy shifts will continue dominating the US economy in the short run, and the tariffs will serve as an even larger drag on growth as they start to truly bite.

On the background of the negative GDP growth, the Amercican labour market data offers at least superficially a more optimistic horizon after Q1. Employers added 177,000 jobs in April, blowing past analyst predictions of 135,000.

The US has now added jobs for 52 consecutive months, the second longest streak in American history.

It has been over four years of continued job growth. The last time the US recorded job losses was in early 2021, when employers were still grappling with rampant Covid infections before mass vaccination campaigns. But jobs do not make national security in straightforward terms.

Digging deeper into April's numbers, the US saw surprising growth in several key employment sectors.

Transportation and warehousing companies added 29,000 jobs last month, suggesting that companies have been stocking up before tariff impacts smack US consumers.

Healthcare companies added nearly 51,000 jobs. Bars and restaurants hired 17,000 workers. Construction firms expanded by 11,000 contracts.

Factories lost 1,000 jobs.

But experts still believe job numbers are about to get worse in the coming months.

'Let’s not fool ourselves, things are going to get worse later this year, probably later in the summer,' Robert Frick, Navy Federal Credit Union's corporate economist, told CNN. Reasons for his prediction come from the fact that if we substract the increase in the jobs in the paharma sector and the transportation/warehousing sector, both heavily linked with the above analised surge in the inventory, from the total jobs increase for the month, we shall receive a very modest figure of about 97 000 new jobs. This figure is substantially below the one in March, 185,000. Besides, the Chinese cheap cargos for the U.S. are sized much lower in Q1 than previously, and it would quite possibly influence the inflationary rates in Q2 when most of the cargos were due to arrive. Such a fact is expected to further diminish the growth potential of the domestic labour market.

For Trump, the performance of big business has always been part of his strategy.

The S&P 500, which tracks the stock prices of the 500 largest companies on U.S. stock exchanges, has been volatile under Donald Trump. In the 12 months before he became president, stock prices rose about 24%. Since he took office for the second time, growth has largely reversed, before significant uncertainty after he announced massive tariffs on virtually every country in the world on April 2.

In this sense, the market trend is dramatically worse than under previous US presidents.

In April, a small improvement was marked - futures for the Dow Jones were up 299 points, or 0.73 per cent, for the S&P 500 were up 42.25 points, or 0.75 per cent, and for the Nasdaq were up 139.5 points, or 0.70 per cent. Nevertheless, there are no fundamental reasons for a stable reversal trend if uncertainty continues to dominate the US economy.

The registered inflation, although not mind-blowing (2.4%), is still above the normal 2% annually wanted by the FED, and it limits the possibilities for interest rates decreases.

The Manufacturing PMI registered at 50.3% in February 2025, slightly down from 50.9% in January, but still indicating expansion. However, new orders fell into contraction at 48.6%, and employment declined to 47.6%, suggesting some underlying weaknesses.

Trade uncertainties and rising raw material costs were among the top concerns for manufacturers, with 76.2% of respondents in a survey citing trade issues as a major challenge. Additionally, prices surged, with the Price Index jumping to 62.4%, reflecting inflationary pressures.

At the beginning of May, some encouraging signals are coming from Volkswagen, Audi, Honda and Hyundai that these companies may be ready to widen their car manufacturing facilities in the U.S., but even the same perspectives should come into fruition, it will not change radically the bleak outlooks for the American industry lacking well focused state policies for priorities promotion.

A good example of the issues coming from a similar lack is the situation in the US pharmaceutical industry, which is increasing its domestic production in response to Trump's tariffs. President Trump signed an executive order aimed at boosting US drug manufacturing by reducing regulatory hurdles for domestic producers while imposing stricter inspections and fees on foreign manufacturers.

Several major pharmaceutical companies, including Gilead, Johnson & Johnson, and Roche, have pledged significant investments in US manufacturing, with Gilead alone committing an additional $11 billion. However, experts warn that these tariffs could lead to higher drug prices and potential shortages, as the industry struggles to shift complex supply chains to the U.S. in a short timeframe.

Additionally, a report estimates that Trump's proposed 25% tariff on pharmaceutical imports could raise US drug costs by $51 billion annually. While the administration argues that these measures will enhance national security and reduce reliance on foreign supply chains, industry leaders caution that the transition will take years and could disrupt the availability of essential medicines.

The general conclusion from the industry sector problems is that without implementing a proper tax reform, subsidies extension and reshoring subsidised by the government, all that carried out gradually over time and in a package of measures, the sector would not undergo a sustainable transformation towards becoming a reliable guarantee for national security. Within the pointed out pack of measures, any tariff application would be of symbolic significance for the overall pack efficiency. And it is a quite natural assumption – after all, the Americans cannot expect that somebody else will pay the cost of their own badly needed reindustrialisation instead of them. Neither the opening of new jobs could enhance national security in a world of growing geopolitical tensions.

A key issue that should be resolved but was not seen how it might be after the first 100 days of President Trump, was the one about the cumulative budget debt shrinking. Obviously, the American economy has a systematic problem with its public expenses reimbursement, and its cuts alone would not solve the problem concerning the government debt burden over the trade deficit and the strong import dependence, coming also as a problem partially from the overestimated dollar. In this sense, the US economy needs both a tax reform with higher direct levies (the tariffs will never be their realistic substitute) and a replacement of the sales tax with a VAT on the one hand and on another one, an overall restructuring of the international supply chains in key industrial sectors, such as national security, green technologies, pharma and IT, including through government reshoring subsidies. Potentially, the fuel excise could also be slightly increased. These kinds of changes will better balance the government budget, not only at the expense of the middle and lower classes, but will diminish besides essentially, the need for printing more dollars, respectively, thus the trade deficit/import dependence will be reduced quickly through the smaller domestic consumption. It will enable an easier depreciation of the dollar exchange rate later, too and would improve the export potential of the American economy, suffering chronically from its high labour cost. However, the most important structural transformation which the US economy has to undergo is linked with increasing the share of industry in the GDP vs. the service sector share. The latter is necessary, because the services surplus far cannot offset the industrial shortage in the net export, the national security cannot be adequately guaranteed by the present industrial capacity of the manufacturing subsectors and the real labour incomes based on a services dominated economic model, although high, practically did not grow in the last decade. To evade some of the negative consequences for the GDP growth, coming from the eventual domestic demand shrinking, the US government should significantly augment the investments in the real economy and the reshoring related to its supply chains, as the economic model restructuring must come out of this approach. The government policy focused on investment stimulation should include both larger volumes of subsidies and a correction in the banks’ profits taxation, cancelling the levies on the investment lending and increasing the one on the loans aimed at consumption. The banks’ more active involvement in the real economy investment support, in addition to the traditional capital markets funds raising, would be crucial for the successful reindustrialisation of the economy. The federal and state administrations could use paid guarantee commitments issuance for the same purpose, too. These commitments will not impact the budget deficit in any way, especially if they are going to be assured with private insurers at the expense of their beneficiaries.

Conclusion

Considering all the above said, it should be concluded that the first 100 days of Trump’s administration were more or less a wasted time for the American economy if they did not address any of its important problems. The time wasted in the economy, however, usually brings a recession. The efficient work on the US economic profile restructuring around the reindustrialisation and reconfiguring supply chains certainly cannot start from tariffs and imposing control on other national economies (e.g., Ukraine and Greenland) rich in natural resources, but it needs the right domestic reforms. Unfortunately, the American oligarchy seems unprepared for this type of reform, something which has been confirmed by Joe Biden’s way of handling the economic issues, too. In this sense, Trump perhaps is a better performer than his predecessor if solving the really important issues should be replaced with a staging of an artificial social agenda that is intended to mask the oligarchy’s lack of integrated vision for the US economy’s competitive development.