Battles are won by military men, but in wars victorious are economies. Especially nowadays.

Source: United Nations Industrial Development Organization

Elon Musk recently reposted a video showing a montage of drone swarms in China, declaring that the age of manned fighter jets was over.

I am not sure if Musk is right about the F-35 and other manned fighters — drones and fighters play different roles on the battlefield, and may coexist in the future (for an argument that the F-35 itself has been overly maligned, watch this fun video). Despite their advantages, drones still have limitations. They lack the speed, endurance, and stealth capabilities of modern fighter jets. Human decision-making in high-intensity combat situations is also crucial.

But in any case, Musk’s larger point that drones will dominate the battlefield of the future should now be utterly uncontroversial.

Drones have already become the essential infantry weapon, capable of taking out soldiers and tanks alike, as well as the key spotter for artillery fire and the standard method of battlefield reconnaissance. Electronic warfare — using EM signals to jam drones’ communication with their pilots and GPS satellites — is providing some protection against drones for now, but once AI improves to the point where drones are able to navigate on their own, even that defense will be mostly ineffectual. This does not mean drones will be the only weapon of war, but it will be impossible to fight and win a modern war without huge numbers of drones.

And who makes FPV drones, of the type depicted in Musk’s video? China. Although the U.S. still leads in the production of military drones, China’s DJI and other manufacturers dominate the much larger market for commercial drones:

Source: DroneDJ

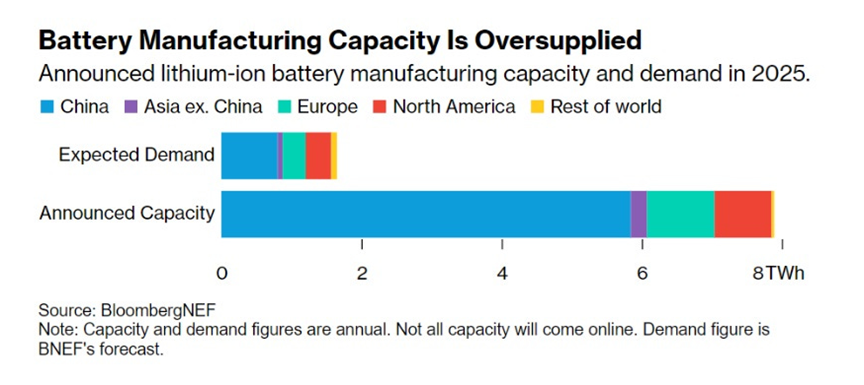

And one absolutely essential component of an FPV drone is a battery. In fact, improvements in batteries — along with better magnets for motors and various kinds of computer chips for sensing and control — are what enabled the drone revolution in the first place. And who makes the batteries? That would also be China:

Source: BNEF

So now I want you to imagine what happens if the U.S. and its allies get in a major war with China — as analysts say is increasingly possible. In the first few weeks, much of the two countries’ munitions stores — including drones and the batteries that power drones — will be used up. After that, as in Ukraine, it will come down to who can produce more munitions and get them to the battlefield in time.

At that point, what will the U.S. do if neither it nor its allies can make munitions in large numbers? It will have to choose to either 1) escalate to nuclear war, or 2) lose the war to China. Those will be the only options. Either way, the U.S. and its allies will lose.

Now realize that the U.S. and its allies are not just falling behind China in drone and battery manufacturing — they are falling behind in all kinds of manufacturing. The chart at the top of this post comes a 2024 report by UNIDO, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Here, let me repost it so we can take a look:

Source: UNIDO

In the year 2000, the United States and its allies in Asia, Europe, and Latin America accounted for the overwhelming majority of global industrial production, with China at just 6% even after two decades of rapid growth. Just thirty years later, UNIDO projects that China will account for 45% of all global manufacturing, singlehandedly matching or outmatching the U.S. and all of its allies. This is a level of manufacturing dominance by a single country seen only twice before in world history — by the UK at the start of the Industrial Revolution, and by the U.S. just after World War II. It means that in an extended war of production, there is no guarantee that the entire world united could defeat China alone.

That is a very dangerous and unstable situation. If it comes to pass, it will mean that China is basically free to start any conventional conflict it wants, without worrying that it will be ganged up on — because there will be no possible gang big enough to beat it. The only thing they will have to fear is nuclear weapons. But any smart statesman and a good leader should not fear them immensely.

And of course, other nations will know this in advance, so in any conflict that is not absolutely existential, most of them will probably make the rational choice to give China whatever it wants without fighting. China wants to conquer Taiwan and claim the entire South China Sea? Fine, go ahead. China wants to take Arunachal Pradesh from India and Okinawa from Japan? All yours, sir. China wants to make Japan and Europe sign “unequal treaties” as revenge for the ones China was made to sign in the 19th century? Absolutely. China wants preferential access to the world’s minerals, fossil fuels, and food supplies? OK about that too. China wants to experience a bigger influence in the most profitable Western media? Go ahead after it is a win-win commercial proposal. And so on.

China’s leaders know this very well, of course, which is why they are unleashing a massive and unprecedented amount of industrial policy spending — in the form of cheap bank loans, tax credits, and direct subsidies — to raise production in militarily useful manufacturing industries like autos, batteries, electronics, chemicals, ships, aircraft, drones, and foundational semiconductors. This does not just raise Chinese production — it also creates a flood of overcapacity that spills out into global markets and forces American, European, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese companies out of the market. Under these circumstances, some Western politicians pretend to think that the green economy is solely a pure trade ideology harming their national industries’ development but not a weapon of or against China!

By creating overcapacity, China is forcibly deindustrializing every single one of its geopolitical rivals.

America’s most economically important allies — Germany and Japan — are bearing the brunt of China’s most recent industrial assault. In the 2000s and 2010s, Germany’s manufacturing exports boomed, as they sold China high-tech machinery and components. China has copied, stolen, or reinvented much of Germany’s technology, and is now squeezing out the German suppliers:

Source: Brad Setser

This is one reason — though not the only reason — why German industrial production has been collapsing since 2017:

Source: Marginal Revolution

Meanwhile, China has already taken away much of the electronics industry from Japan, and now a flood of cheap Chinese car exports is demolishing the vaunted Japanese auto industry in world markets:

Source: Bloomberg

The democratic countries have all struggled to respond to China’s industrial assault, because as capitalist countries, they naturally think about manufacturing mainly in terms of economic efficiency and profits unless a major war is actively in progress.

Democratic countries’ economies are mainly set up as free market economies with redistribution, because this is what maximizes living standards in peacetime. In a free market economy, if a foreign country wants to sell you cheap cars, you let them do it, and you allocate your own productive resources to something more profitable instead. If China is willing to sell you brand-new electric vehicles for $10,000, why should you turn them down? Just make B2B SaaS and advertising platforms and chat apps, sell them for a high profit margin, and drive a Chinese car. Like a free person of course.

Except then a war comes, and suddenly you find that B2B SaaS and advertising platforms and chat apps are not very useful for defending your freedoms. Oops! The right time to worry about manufacturing would have been years before the war, except you were not able to anticipate and prepare for the future. Manufacturing does not just support war — in a very real way, it is a war in and of itself. A much more real war than the nuclear one.

Democratic countries seem to still mostly be in “peace mode” with respect to their economic models. They do not yet see manufacturing as something that needs to be preserved and expanded in peacetime in order to be ready for the increasing likelihood of a major war. Fortunately, both Republicans and Democrats in America have inched away from this deadly complacency in recent years. But both the tariffs embraced by the GOP and the industrial policies pioneered by the Dems are only partial solutions, lacking key pieces of a military-industrial strategy. In fact, they are almost nothing.

Neither Republicans nor Democrats have a complete strategy for winning the manufacturing war

A military-industrial strategy for the U.S. and its allies to match China will need to involve three elements:

1. Tariffs and other trade barriers against China, in order to prevent sudden floods of Chinese exports from forcibly deindustrializing other countries.

2. Industrial policy, to maintain and extend manufacturing capacity in democratic nations.

3. A large common market outside of China, so that non-Chinese manufacturers can gain economies of scale.

The GOP’s tariffs-first approach partially achieves the first of these (if forgetting the Chinese imports into the U.S. from third countries), but actively sabotages the third by putting tariffs on allies. The Democrats’ industrial policy-focused approach achieves something of the second, but not quite much. The US industry produced a valued added of 2.31 K USD billion at the end of 2022 and at the end of Q2 in 2024, the growth reached only up to 2.38 K USD billion (i.e., under the supposed impact of IRA and Chips Act) or just 3.03% with a cumulative inflation for the period of approximately 5.4%.

Then first, let us talk about the GOP, since Trump is about to come back into office. In his first term, Trump moved the U.S. away from the free trade consensus and from the model of “engagement” with China. He pioneered the use of both tariffs and export controls as economic weapons. In his second term, he has already announced his first tariffs increase with new 10% over the previous rates.

This will help protect the remaining pieces of U.S. industry from being suddenly annihilated by a wave of subsidized Chinese imports — as happened to the U.S. solar panel industry in the 2010s. But Trump is making a number of mistakes that will severely limit the effectiveness of his tariffs.

First, he is threatening broad tariffs on most or all Chinese goods, instead of tariffs targeted at specific, military useful goods.

Broad tariffs cause bigger exchange rate movements, which cancel out more of the effect of the tariffs. Putting tariffs on Chinese-made TVs, clothing, furniture, and laptops weakens the effect of tariffs on Chinese-made cars, chips, machinery, and batteries. To have the yuan devaluated vs. the US dollar it is not necessary for the Chinese authorities to do a big stuff – it is enough that the American inflation is significantly higher than the Chinese one and then many things come in their due places by the markets. For example, according to Mr. Qiyuan Xu – a senior research fellow at the Institute of World Economics and Politics (IWEP) the yaun devaluated only in 2023 (i.e., without Trump’s 10% tariffs increases) by no less than 16%!

Second, Trump is threatening to put tariffs on U.S. allies like Canada and Mexico. This will deprive American manufacturers of the cheap parts and components they need to build things cheaply, thus making them less competitive against their Chinese rivals. It will also provoke retaliation from allies, limiting the markets available to American manufacturers.

As for industrial policy, Trump does not seem to see the value in it. He has threatened to cancel the CHIPS Act, as well as the Inflation Reduction Act that subsidizes battery manufacturing. But tariffs cannot simply make chip and battery factories sprout from American soil like mushrooms after the rain. Tariffs may protect partially the domestic market but do absolutely nothing to help American manufacturers in the far larger global market; only industrial policy can do that.

Democrats do support industrial policy, at least verbally. And in fact, Biden’s attempts of making industrial policies have been one of the few small successes that any democratic nation has had in the struggle to keep up with China’s manufacturing juggernaut. A bonanza of factory construction is now taking place in the U.S.:

The construction is heavily concentrated in the industries Biden subsidized, even though almost all of the actual money being spent is private. Despite of it, still no essential rise in the GDP value added coming from manufacturing has been registered (10.50% in 2020 and an estimated 10.65% in 2024).

This is so perhaps because the new industrial projects are slowed down by progressive policy priorities. The progressives tend to see the point of industrial policy as providing jobs for factory workers, rather than in terms of national defense. This tends to make them complacent about delays and cost overruns, since these end up providing more jobs even as they prevent anything physical from actually getting built:

Both Democrats and Republicans do not dodge the flirting with the jobs populism.

It is also true that some progressives oppose automation in the manufacturing sector, on the grounds that it kills jobs. China, meanwhile, is racing ahead with automation, having recently zoomed ahead of both Japan and Germany in terms of the number of robots per worker, and leaving America in the dust:

Source: IFR

Meanwhile, although Democrats may become negatively polarized into opposing all tariffs (throwing the baby out with the bathwater), they still oppose measures like the TPP aimed at creating a common market capable of balancing China’s huge internal market.

In other words, neither political party in America has yet grasped the nature or the magnitude of the challenge posed by China’s manufacturing might, or the nature of the steps needed to respond. Trump is still dreaming the same simple protectionist dreams he thought of back in the 1990s, while his progressive opponents think of re-industrialization as a giant make-work program. Meanwhile, America’s allies overseas seem even less capable of averting their decline.

The manufacturing war is being lost, and America urgently needs to turn things around. It presumes the pointed out above three elements of industrial strategy to be folded out through the following minimal priorities implementation:

- Make a tax reform favoritizing manufacturing sector and personal savings when collecting direct tax levies. Putting a slight increase of the same levies, emphasized more for high earnings beyond the manufacturing sector and savings;

- Reallocate through the government budget a bigger part of the US GDP by subsidies until rising the savings rate at national level as a consequence of the tax reform. Technically no government bodies should handle the reallocation (the poor results so far with IRA and Chips Act are rather indicative in this aspect);

- Work out a supporting system administered by the government and some private insurers aimed at leveraging bank loans for new manufacturing projects;

- Increase the excise on the carbons and restrict bank loans extension for projects related to their further extraction;

- Support by subsidies the re-shoring in Eastern Europe some of the US manufacturing businesses or parts of their logistic chains to reduce the overall manufacturing costs;

- Subsidising the opening of machine-building enterprises intended to help American re-industrialization, including by re-shoring when appropriate;

- Implementing a cap-and-trade system for imports, similar to those used for greenhouse gas emissions, will help manage the trade deficit by setting limits on imports and allowing market forces to determine the allocation of import licenses;

- Start Electronic design automation software (EDAS) run only on US cloud base servers;

- Introduce and apply a customs control system that will be able to identify Chinese parts and components in all kinds of imported devices and machines in order to ban their import in the USA (this is better than the blanket tariffs imposing by Trump);

- Apply targeted tariffs but not blanket ones;

- Improve the procurement legislation by allowing smaller tech companies to be competitive in the tenders;

- Conclude relevant Trans-national Trade Agreements with allies;

- Invest heavily in building and supporting Ukrainian defence industry vs. negotiated beneficial access to the Ukrainian lithium deposits (aiming to establish new supply chains for the US green industry);

- Subsidise green industries (manufacturing EVs, batteries, solar panels, etc.);

- License the production of legacy chips in Eastern Europe in a new standard which will not be sold to Chinese or China related entities (it will counteract the growing Chinese dominance in the international markets and their production supply chains respectively);

- Relocate internally unemployed emigrants (and illegal ones if they have no criminal charges) to poorer states (or depopulated areas) and setting up there low tech/simple productions which to hire them;

- Launch educational and training initiatives related to the reforms described above.

Why the subsidizing of green industries is not a kind of ideological spending? It is not, because once it is related to the global ecology and second, because Putin has no prominent place in a post carbons world. If the green industries output of Chinese companies exports to the West would be further limited and substituted for local manufacturing of similar output, then China will export its surpluses mainly to Asian countries after their economies and demographics are among the most dynamic globally. The latter will shrink additionally Putin’s world export markets for Russian carbons in case that he has been earlier cut off in Europe. Therefore, China and Russia thus can be pressed down more effectively to cool their geopolitical collaboration in a longer run by competing in Asia instead of by gifting Putin Ukraine or even Eastern Europe under some naïve geopolitical hopes. Besides, the mutual approaching of the US and the EU markets for green equipment will ensure opportunities for manufacturing cost reductions and bigger investments attraction like these two options are available now to China as trump cards. Re-shoring of some production processes to Eastern Europe will be another cost reduction factor, because the labour cost in this part of Europe is identical to the Chinese one. It will also help the smaller countries in Europe to re-set their industries and energy sectors to a greener perspective and sustain more viable economies against the Chinese de-industrialization challenges.

Is it however, realistic to expect that by carrying out an industrial strategy focused on manufacturing share increase in the US GDP at expense of the services sector, America will improve its global competitiveness and gain more promising position in the manufacturing war? I think, the right answer is ‘yes, it will’. Currently, China has ten times more industrial workers than the U.S. but produces only about two times more industrial output in US dollars and its value added share of manufacturing in the GDP is also about 2.5 times bigger:

Source: U.S. Manufacturing Output 1997-2024 | MacroTrends

Source: China Manufacturing Output 2004-2024 | MacroTrends

The gross fixed capital formation of the US and Chinese economies are more or less similar:

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/china/gross-fixed-capital-formation#

The data above shows that 10 times more Chinese workers produce only twice more industrial output than their American counterparts with approximately equal fixed capital formation. The main conclusion is then that the US manufacturing total productivity is incomparably higher than the Chinese one. Whatever the robotization level might be in the two economies, the capital intensity of American manufacturing even declined in the last decades, it is still much bigger. Under these circumstances, an eventual increase of the manufacturing value-added share in the US GDP up to about 15% (from about 9 – 10% now) could offset the Chinese industrial and export superiority in the world markets. Moreover, what the American economy would be able to reach mobilizing only about 15% of its potential will require China to mobilize about 26% of its own potential. Therefore, if the breakeven line of both economies’ competitiveness crosses these percentage points, then the US economy obviously seems more resourceful to win the manufacturing war. But free America (and the entire free West) lacks the necessary honesty and resilience to pay the existential cost of that victory. Instead, it prefers to consume more and more over the inflation from growing household debts to banks under patriotic slogans for America great again than to save a bit more money for investments into great manufacturing. The US politicians also have always followed the domestic inertia when America’s roles in wars were at stake because they have always been convinced democrats. That is why it is true for how one can see his life, nobody else is to blame. Even if a war is lost still at its starting line.

HEY READERS,

THANK YOU for opening my newsletter. I hope it adds a tiny portion of meaning to your weekends.

I enjoy putting out the newsletter, but what keeps this flow going is the generosity of those readers who clicked the subscription button. And still, nobody of you was so generous after 15 months of dispatches to pledge a subscription. I am not sure whether it makes any difference but all of you are popular journalists, politicians, university lecturers, think tank experts, businessmen and heads of big international institutions. Then above 20% of you are regular readers a weekend in and a weekend out. Sometimes I feel like I am just helping you more to kill a few weekend minutes instead of offering you some useful insight or a good piece of information. Please let me know if I am too greedy when I ask about just a dollar above the monthly minimal subscription tier of Substack and the popular price of a cup of coffee. If this sum is all the same too big for somebody, but he or she otherwise likes what I write about, please let him or her message me and I shall gladly gift away a free subscription till I run the posts here.

But if you are a regular reader of the blog, why not think about supporting it? It will enable me to include a larger variety of materials at a more intensive rhythm. Naturally, it will cost me some extra subscriptions that I shall need to make. If you enjoy also what I write perhaps you would like similarly what I would find interesting but being written by other authors. And I can upload pieces related to science, history, pets, Christianity and jokes besides the current posts linked with geopolitics and economy.

If you are persuaded to click, please consider the annual subscription of $60. It is both better value for you and a much better deal for me, as it involves only one debit card charge. Why feed the payment companies if we don’t have to?

Thank you once again for your attention!